There are basically two schools of thought regarding the intentions and impacts that so-called emerging donors like China, India, Iran, and Saudi Arabia have on other developing states. One camp argues that emerging donors have nefarious designs on exploiting their fellow industrializing nations. These skeptics contend that emerging donors use some of their newfound wealth to fund development projects abroad that are primarily intended to benefit the lending country through the cultivation of new markets for exporting goods, acquisition of natural resources for manufacturing and energy, and extension of political spheres of influence. Unlike traditional donors such as the US, World Bank, Japan, France, Germany, and the UK, these new actors on the scene do not impose strict human rights, labor, rule of law, or environmental standards on recipient states, thus enabling anti-democratic governments and retarding progress toward Western conceptions of development (Naím 2009).

The other camp argues that claims of ill intentions and attempts to subvert democratization on the behalf of these emerging donors are overblown. China, for example, does not have a readily identifiable development assistance reform package like the Washington Consensus model that prescribed specific institutional and economic changes that countries would need to undertake in order to obtain funding from traditional donors. Some have even declared the idea that a separate "Beijing Consensus" (Ramo 2004) exists a "myth" (Kennedy 2010). Furthermore, empirical scholarship on the relationship between political factors and aid distribution has demonstrated that China is no more likely than Western donors to steer money toward countries based on their politics, and the Asian giant does not deliberately invest in countries based on their availability of natural resources (Dreher and Fuchs 2015; Gellers 2017).

Among emerging donors, China has grown to become a force on the world stage. In 2011, China overtook the World Bank to become the largest lender to developing countries in the world. Interestingly, however, China has a long history of working with or lending to other less-industrialized states. For instance, China has provided development assistance to other countries since 1950, and its approach to foreign aid (i.e. mutual benefit, respect for sovereignty, and self-reliance), was articulated by Premier Zhou Enlai in 1964.

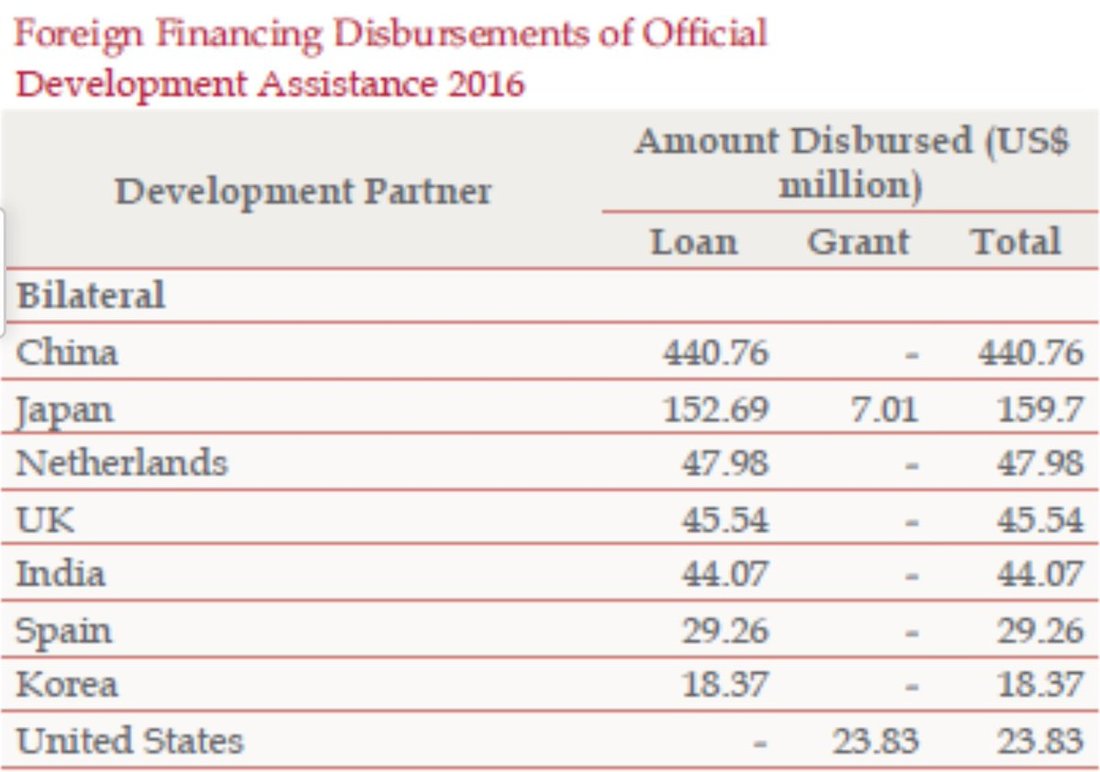

The Sino-Sri Lankan relationship dates back to 1952, when China signed its first trade agreement with a non-communist state, Ceylon (the previous name for Sri Lanka). This Sino-Lanka Rubber Rice Pact signaled the beginning of an important economic partnership in Asia. Today, China is the largest lender to Sri Lanka. In 2016, China loaned Sri Lanka over $440 million, $100 million more than the World Bank and almost $300 million more than the next largest lender, Japan (see below).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed